North Estonian Klint and some of its analogues

The Baltic Klint is not the only system of erosional escarpments in the world, in Europe and not even on the Baltic Sea. The best known escarpments, and also the ones most similar to the Baltic Klint, are the three escarpment systems running on the “island” of Ontario in the area of the Great Lakes in North America, to an extent in the boundary area between the Michigan Syneclise and the Canadian Shield: Black River, Niagara and Onondaga Escarpments. A fourth one, the Helderberg Escarpment, is located in the same region but somewhat farther from the shield.

Black River Escarpment, which extends from the Penetang Peninsula (in the west) to Kingston City (in the east), is the northernmost of the above escarpments and most similar to the Baltic Klint by its location, running along the southern border of the Canadian Shield. By all other features, this 5–15-m-high (max. 25 m) and relatively flat, mostly buried escarpment eroded into Middle Ordovician Black River limestone, is inferior to the Baltic Klint.

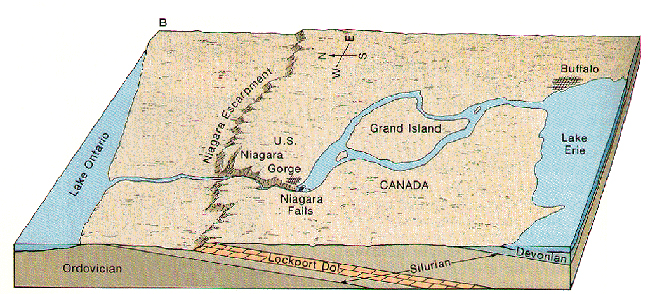

Niagara Escarpment is mightier and more entrenched than the former. The over 750-km-long escarpment begins at east of the Niagara Falls in New York State and runs from there to Tobermory Town on Lake Huron, Bruce Peninsula. The up to 50-m-high main escarpment was shaped mostly by an over 20-m-thick body of harder dolomitized riff limestone overlying the softer Silurian clay shales. It is from this escarpment that the Niagara River plunges down over the world famous Niagara Falls. The original falls were located more than 11 km southwest of the present ones, as this is how long a canyon the river has left behind over the 12 000 years of its retreat in the post-glacial period.

Niagara Escarpment.

Onondaga Escarpment, which runs a few dozen kilometres south of and largely parallel to the Niagara Escarpment, is mostly buried and barely visible in the topography. In terms of its analogy with the escarpments on the Baltic Sea, the Onondaga Escarpment is somewhat comparable to the Devonian Klint.

Helderberg Escarpment in Albany County, New York State, is up to 300 m high and traceable over more than 100 km. The escarpment exposes rock complexes from a nearly 70-million-year time period (Middle Ordovician to Early Devonian), representing a moderate-grade slope in which harder Coeymans (Devonian) and Onondaga (Silurian) limestones are distinguishable as escarpments a few dozen metres in height.

Helderberg Escarpment.

Silurian Klint or Gotland–Saaremaa Klint is the second remarkable coastal escarpment system in the Baltic Sea area. Just like the North Estonian Klint is part of the Baltic Klint, the Saaremaa–West-Estonian Klint is part of the Gotland–Saaremaa Klint. Just like the Baltic Klint is named also the Cambrian-Ordovician Klint after the rocks that it is abraded into, the Gotland–Saaremaa Klint carries also the name Silurian Klint (Miidel 1997). The Silurian Klint, too, starts from the sea bottom app. 20 km south of Gotland Island, that is, 30–40 km east of the Öland Klint. From there it runs north for app. 180 km along the west coast of Gotland, turning northeast from the northern tip of Fårö Island and ultimately disappearing on the sea bottom. After an about 200-km-long journey at the bottom of the Baltic, the Silurian Klint reappears onto the land on the Tahkuna Peninsula on Saaremaa and runs along the northern coast of Saaremaa and Muhumaa to mainland Estonia. The chain of bedrock elevations starting from the southern coast of Matsalu Bay and running in an arc shape up to the vicinity of Vändra (Mõisaküla Salumägi, Salevere Salumägi, Lihula, Kirbla, Mihkli Salumägi) marks the course of the Silurian Klint in mainland Estonia.

The Silurian Klint has been shaped by differences between hard riff lime- or dolostones (Jaagarahu or Jaani Stage) in the upper part of the escarpment and softer marls or clayey limestones (Jaani Stage) at the foot of the klint. Just like the Baltic Klint gets buried under Devonian sandstones on the Syass River, the same happens to the Silurian Klint in mainland Estonia near Vändra.

Silurian Klint at Saaremaa (Ninase Cliff).

Devonian Klint lies south of the Silurian Klint and runs for 200 km, predominantly at the bottom of the Gulf of Riga, constituting a chain of escarpments abraded into Devonian sandstones and marls. The modest escarpments on the east coast of Ruhnu Island and in the southeasternmost part of Estonia near Tiirhanna could also be regarded as part of the Devonian Klint.

Devonian Klint on Ruhnu Island.