Backyard Potterer’s diary - 26.03

Written and illustrated by Tiit Kändler, teadus.ee

Trasnlation: Liis

It is a known fact that not only man has changed the face of the yard. Bluegreen algae and earthworms have changed the face of the planet. Thus also the face of the yard. But has language too changed the yard’s face? When we say ”yard” does something in the yard change? When the earthworm operates, silently, things do change. It only seems to the Potterer that he is doing something with the yard when he talks about it to his love. ”Shovelled snow, split logs, picked up a broken pine branch.” In fact he has done something in his mind. Snow, logs, pine branch, the yard are in the Potterer’s mind, inside the mind, but the yard doesn’t blow hot nor cold about the Potterer. A little hot, maybe. Today the Potterer burnt logs in his stove. As one consequence nourishing glasshouse carbon dioxide gas burst into the yard. The Potterer now sincerely hopes that breathing is that much easier for the plants and maybe it is a little warmer too. When will these nightly night colds end?

We have an amount, a set, of words. Is it an infinite set? What are its sub-sets? Language is a set. Words are its sub-set. Language is likely to be an infinite set. What is its power – is it as with natural number sets or real number sets? How do we know that a speaker of a language ”unknown” to us speaks in a language at all? That his language is from the same set as ours, that our languages at least belong to a common set.

Snakes are most of all feared by city inhabitants. Backyard Potterers don’t much fear them, they have occasionally come across snakes and know that they don’t fly nor do they rush to attack.

We know that trees don’t walk. But do we need an infinite number of trees to prove that? We know that some sound combinations mean something, as for instance “õu” but do we test an infinite number of pronounciations to prove it? How do we know that some have a meaning, some have not? That “õu” has a meaning but “õi” does not? Or maybe it means something in another country. Grass trimmer or grassroot level once did not mean anything, they were simply senseless sounds.

To know the language of birds. To know the language of the yard. The Potterer’s dream. Indeed, at least to know the language of the computer.

Lewis Thomas (1913–1993), American physician and essayist: “Language is what childhood is for.” Mathematics is the language that all sciences speak. Is mathematics also what childhood is for? Or maybe indeed the yard is what childhood is for? And for the Potterer the yard is a kind of prolonged childhood?

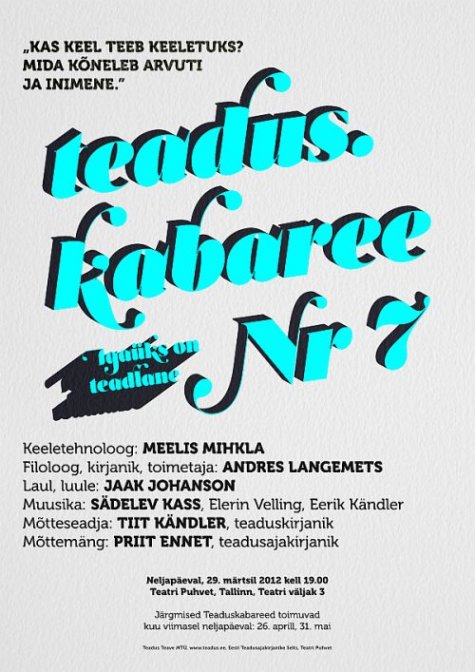

A science cabaret is arranged on Thursday (March 29th):