Alam-Pedja tales: Memories from Palupõhja village

Helgi Velja, mistress of Jõesaare farm, talks to Pille Tammur

Photos from Helgi Velja’s photo album

Translation Liis

Palupõhja nature school in winter 2012. Photo: Arne Ader

As I step out of the door of the Palupõhja nature school the drumming of woodpeckers meets me. In spite of the quiet snowfall the approach of spring is heard and felt. I am in the centre of the peace and tranquillity of the Alam-Pedja Nature Reserve area.

It is difficult to decide if the Palupõhja village in Alam-Pedja should count as a forest or riverside village. After all, it is located in forests but also at the bank of Suur Emajõgi river and its wide water meadows. As many Estonian villages, it has lived through all sorts of times. In an old map the oldest date is found, 1601. More is known of life before and after the Second World War, when there was a school and a brass band. Here are parts of a conversation with the only inhabitant of the village who still remembers life then, to give an idea of it.

***

Helgi, for how long did you manage to live here at a stretch?

To start with, things turned out so that I went to secondary school in Puhja, but to elementary school in Palupõhja. We went to take the 4th grade exams at Puhja, because just for the sake of two students the commission would not travel here.

Our teacher was Asta Sommer (later Asta Karjane). Earlier the school was in the forester’s house, it doesn’t exist any longer. There was a long table and benches along it. But at Jaago we already had school desks.

Palupõhja school children in 1949. In the photo the 2nd class students and teacher Asta Sommer

When you were studying in Tallinn later, how often did you get home and how?

I could get home when mother sent money for the journey. The last stretch was from Puhja to home, on foot, step by step, your packs on back, crossing the river on the Reku raft. There were no thoughts such as, I can’t make it. If you wanted to get home then you got home. Later I had a bicycle at the barn at Jaanson’s Vello’s place. If you were by foot then all who went in the same direction –by horse of course, not by car – always picked you up. Everybody knew that a walker should be picked up. You were taken along gladly. When we went to school we were always picked up, in winter too. We stood on the sledge runners, a fine trip, and when cars came during the Soviet period we were also picked up, you just jumped on to the car, bang.

I had beautiful plans but mother said, I can’t manage to keep you at school: a single woman cannot manage, everything was taxed and in addition the norms – simply crazy … There was the Leedi kolkhoz, in general they simply wanted to centralize everything. The forced resettlements were so many that they can’t be counted. Even when the Reku state fish farm was established, even then they wanted to get us away. Well, the fish farm was anyway built in order to hide the missile base that was to be established here, but, well, we know how that turned out. Mother’s main income was from honey; it was exchanged for bread flour. Meat was from our own cattle barn, from the forest we didn’t get any, the forest was empty of animals. Wild animals could not be relied on.

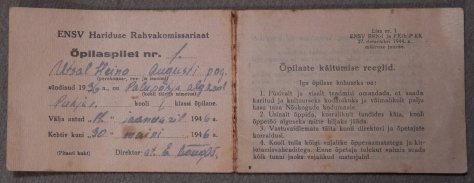

Student ticket

Where were celebrations held in Palupõhja village?

The celebrations were usually at the Jaago farm. Before the Soviet period - the master was very nationalistic – he organized balls. There were Palupõhja dances. My mother went there too. They were held in spring, and the shared work tasks always ended with a dance. Hard work the whole day. Not like now when you work for a few hours and then go flat on your back. From daylight to daylight there was work, then you washed yourself at the well. It was in the warmer period. Usually a large wooden water tub beside the well was always full of water and standing there in the sunshine it was nicely warm too.

Was there something like soap too?

I think there was, my mother always boiled soap herself. When a piglet was slaughtered there was fat adhering to the intestines that was not used for food: it was collected and boiled into soap. Boiling soap was also a common thing at that time.

Did the workers bring special clothes for the dances?

Well, of course, clean things had been taken along and shoes were put on. There were plenty of people who played instruments in the village and music thundered.

Was the ball at the farmhouse where the voluntary work was at the moment?

Mostly the balls were at Jaago. There was this large room where the school class was held later. A long table was put there and food laid out. Beer was brewed and music played and the party was on.

If you were to compare things then and now - How do you see the youths at the nature school now, do they understand nature?

There are no hooligans, so it is still not too bad. Some are interested, some not, but they listen to it all with the others and something stays in memory too. But they get served too much readymade goodies: papers on the table and you just answer Yes and No. Don’t they have heads? You should look for yourself and find out and discover... This learning has been made too easy for them. It happens too that some can’t manage their flocks of children. Once a young mother came early with her little boy. The mother knew nothing about heating with a stove or using an outdoor toilet, but the boy was smart, knew how to ask why it was done like that and how this thing worked. Well, probably they had never needed these thing before in life.

From that point of view we are still in a lucky position in the sense that we still have a continuity that hands on how to manage the most basic things: heating with a stove, lighting a fire, caring for a garden bed, and so on. But this chain is already very fragile, nearly at breaking point, like this last story showed. What to do so that the knowledge and the skills are preserved?

Yes, three years ago they made garden beds at the nature school but not so that it suited this soil. The thing is that there are no longer any country grandmothers. It would be fine if there would be such an option. Actually this would be a very strong support, if these grandmothers were kept nicely in the country: children could go to the country, to grandmother, and computers must stay at home. No grants would be given if a computer and smart mobile were at hand.

***

So, if even one winter-time inhabitant remains in a village I would have him or her very strictly protected: so that she would be able to live peacefully and keep busy with her things because the amount of knowledge and culture that she keeps alive and shares is awe-inspiring. Whether we have the wisdom to learn from her is another issue.

From the Palupõhja village story and the Jaago farm and nature school stories it can be deduced that if things develop until a village has no inn nor church but there is a school, here the Palupõhja nature school, then all is not lost. The most vital thing remains - hope.

Looduskalender’s Alam-Pedja tales are supported by the Keskkonnainvesteeringute Keskus (Environmental Investment Centre).