Backyard potter's tales

Backyard Potterer's diary. February

Written and illustrated by: Tiit Kändler

Translation: Liis

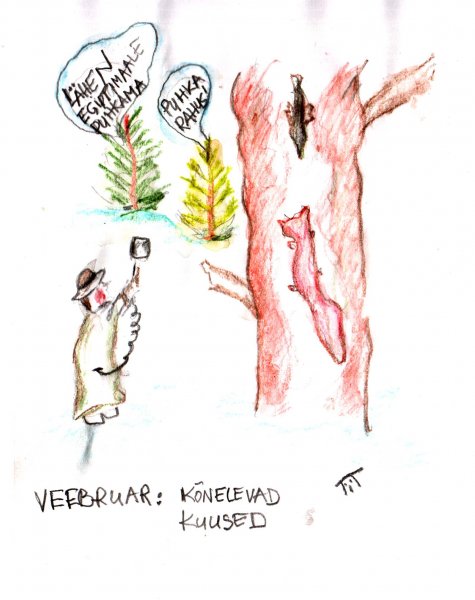

February: Talking spruces. - "I'm off to Egypt for some rest and sun." - "RIP!"

There is a Finnish tale with the neat title “Talking spruces“. When a hunter lit his fire under a spruce in the forest the heat distressed the snake in the top of the tree and it begged to be helped down. When the hunter had done so, the snake in return taught him the language of animals. Such things always happen in folk tales. But besides the language of beasts the snake also taught the hunter the language of plants. Which was particularly enviable. Animals make sounds and move, and their language and body language is after all to some lesser or greater extent possible to learn. Which every pet lover knows. It is more complicated with plants. They make sounds but that is rather from the wind or the force of gravity. And yes, they move but for this too they get the power from the sun, and the winds and rains, snows and hails born from it.

The tale of the talking spruces goes on to tell that the man lay down to sleep under the spruces and heard one spruce moaning to another that it would fall down and die this night, and begged the other to support it. The other spruce refused because it had guests sleeping under it – the dog and the hunter. And then a gust of wind went through the forest and the spruce that had told about its death fell with great crashing. And the spruce with the hunter’s fire at its feet sighed: “Well, so now you fell then, my brother in growth! On a treasure you lived, but on a treasure you died too.“. In the morning the man went to investigate the fallen spruce and found under its roots a copper casket gone green, but full of gold and silver coins.

February is a month that seems made for pondering on the language of the courtyard plants. The spruces hunch silently as in no other month. The air is pure and bright even when the sun busies itself somewhere in the world behind the clouds. The deciduous trees, that at the moment rather are bare osseous trees, don’t give any indication at all of their talk, excepting willows that bring out their catkins with mad regularity. However, the spruces, somewhere in their depths, talk of the water under their roots, the pines remember with horror the days when the heavy snow masses threatened their branches. For both these tribes the winter has turned their needles greyish, and yet it is the only greenery that the eye can find.

Except for the spotted woodpecker that has appeared in the courtyard again and in whose plumage even some green might be detected, with a good will. It turns out that the feathering of birds did not evolve for the use of flying but developed on the long-ago forefather of the woodpeckers, the dinosaur, long before it got into its head to lift itself into the air. Why on earth – who knows. Even the scientists who believe themselves to be clever think that it was for the sake of vanity. Quite as men these days swagger and display their Mercedeses to women, so the dinosaur flaunted its feathers.

The trees talk and crack and bang in the frost in which the birds however still get on with their flights. Their pilots don’t go on strike. Some birds are charge fliers, dash along a quite straight path from the bird feeder to the nearest spruce branch. Others however – as the blue tit and the crested tit – are sinus fliers who draw their air path as a neat trembling wave line.

The February moon, even when it isn’t quite full, has nearly turned itself over as if it were full. Dogs howl in the cold and the snow does duty as thermometer – the sound from under your feet tells how cold it is.

On the full moon Friday in mid-February one can read that the solar eruptions have grown more violent. The X rays arrive from the sun to the yard in 8 minutes, the solar wind uses all of 4 days to send its electrons and protons into the yard. If the sun electrons could be tempted into a conductor there would be no need to buy external electricity. Worth thinking about. Until then heating must be done with logs but sometimes it seems that the more firelogs that are burnt the colder it gets. At least in the courtyard. And then there is this thing that on one hand the piling of spruce and pine, birch and ash logs into the fireplace seems like a green and recyclable business. But on the other hand one can read that burning wood spews particulate matter into the air, and horrible if for instance the woodpecker would breathe that, it might get cancer and what not more. Anyway, who knows who devours whom, the woodpecker the cancer, or the cancer the woodpecker.

When the cones at the spruce top begin to reflect the sun, then spring isn’t far away, that is evident. The scientists have stirred their brains and found out that the brain never rests. Even when a human sleeps the brain is busy with creating and storing relations known only to itself; that can be compared to mathematical calculations. The brain in its stand by or still state uses only a little less energy than needed to help the Backyard Potterer to hit a tree log with the axe in order to split it. In the resting of the brain there is power and force that is needed for it to be ready at every conceivable moment. Honestly, it would not be at all nice if you for instance, while lazing in your armchair, suddenly would want to drive off the fly on your forehead – but the brain would need about as much time to prepare this operation as some international organisations need for starting interventions in warfare situations.

So the brain must be on alert all the time and the proportion of this dark energy is roughly as large as the proportion of dark energy in universe vis a vis the energy known to us. Ever three-quarters dark energy to one quarter of energy known to us. Interesting that it is the same with humanity. One fourth are splendid and clever and rich according to themselves, three fourths are some sort of dark force.

So it is with the February yard too. On the surface it doesn’t talk, but the stand-by status, the silence of the yard, is deceptive. Somewhere down there in the depths life burgeons and at least three quarters of what our eyes can see and ears can hear takes place.

Since the plants seem to be content the question comes up why precisely February is so short, the shortest of months. May for instance is much shorter by name. Investigation of the matter shows that we owe this to the pagan festival of Numa, the king following Romulus. Our calendar story is long and thorough but put briefly the thing is that Romulus was wiser than we. He not only laid the foundations of the city of Rome, but also the calendar. And of course there were ten months in the year then. Why else is the name of the last month December or the tenth? The year began in March, September was the seventh, October the eighth and November the ninth month. Numa came, and confusion started. He tried to harmonize the calendar with the phases of the moon and added January and February. Devil knows why to the beginning of the year. And in February he set the heathen cleansing festival and decreed that the length of the month was to be 28 days. In order to coordinate this mess with the solar year, Julius Ceasar had to distribute the leftover 10 days among the months. But they were 12. Luckily the length of February could be left as it was, thanks to the pagan festival. Then Marc Anthony came and named the quintilis July, whereupon Octavianus or imperator Augustus let all men be taxed and counted, wherefore Joseph must go to Betlehem and his wife Mary came to give birth to Jesus just there. From here on the sextile became August, and it had a day tagged on it but not even the Christian Gregorius dared to touch the pagan February on setting up his calendar.

Which of course now only makes us happy because the coldest month of the year is the shortest. And from Estonia’s Independence Day there are some good few days less to spring than there would have been without the Roman pagan festival.

Be it so or otherwise, but after this story a squirrel suddenly jumped on to the trunk of the some two hundred year old pine huddling outside the window, scared off the nuthatch from there and waved its indescribably-coloured tail to boot.

In the Finnish tale of the speaking spruces the hunter did not only find a treasure beneath the spruce but also a fox, killed by a spruce branch run through it. So the hunter found both riches and hunting prey at one take. Which shows once more that the Finno-Ugrian practical mind does not limit itself only to some abstract and fluctuating values or gold or a nominal year circle. Fox fur can always be wound round one’s neck and the world and weather are at once warmer.