The wolf in the Folk calendar and place traditions

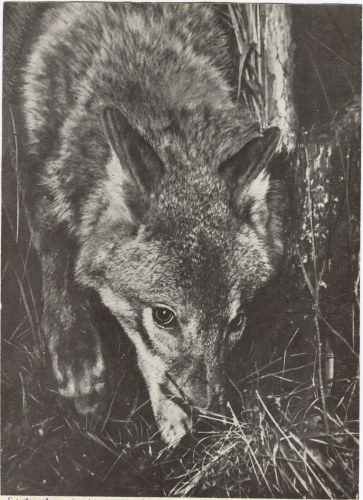

To the village for a dog. From journal Neue Baltische Waidmannsblätter, 1/1912.

The wolf in the Folk calendar and place traditions

In the Folk calendar the wolf has a significant role, Marju Kõivupuu writes in journal Loodusesõber. As the only wild animal it has its own month – February. In fact people have called both January and February wolf months, because the wolves’ period of heat is in mid-winter, and they are seen and heard more.

The name wolf month can also be found in the Wiedemann Estonian-German dictionary*. Wolves frequently kill dogs in winter; people of old accounted for it or explained it by the need for a female wolf to eat dog meat during the heat period or she would not become with young.

“Wolves used to come to the farms in the old days in the Candle month to get fertility from dogs: if the female wolf had not had dog meat then she would not bear young. They were sometimes six in a row, moving in each other’s tracks in the snow. The next day the tracks were checked – only one set of tracks , but in the night a long row had passed. So dogs had to be shut in during the candle month or the wolves would have “wolfed them down“, carried them to a field and torn into pieces.”

(Tarvastu parish, 1931.)

(Tarvastu parish, 1931.)

Mothers were told not to wean off a child in the wolf month, because the child would then grow into a wanton, loose-mannered person.

The sap month – the month of wolf preventive magic

St George’sday (Jüripäev), April 23rd, is also tied to wolves. In the Folk calendar it has also been the traditional day for letting out cattle to pastures in addition to being the beginning of the economical year and the day of concluding contracts. St George has been held to be the ruler of wolves who kept the jaws of wolves in irons from St George’s day onwards so that the predators could not harm livestock. People believed that St George threw food to the wolves from the sky, in some areas was thought to be the “cloud lumps“, jelly-like matter of unclear origin on the ground.

According to beliefs the fallen so called cloud lumps were toxic to men and all other animals except wolves and caused an incurable disease - rabies.

According to beliefs the fallen so called cloud lumps were toxic to men and all other animals except wolves and caused an incurable disease - rabies.

In Simuna parish the shepherd prepared a special rowan-tree cane before St George’s day and read wolf prevention words over it in the making process:

Saint George, Saint George,

hold fast your dogs.

Set bridles on their heads,

Irons in their mouths.

hold fast your dogs.

Set bridles on their heads,

Irons in their mouths.

St George’s fires were also lit in order to fend off wolves from domestic cattle in the grazing season. For the symbolical fending off of wolves guns were fired in many places on that day, and loud noises were made. Likewise many other different preventing magic rites were undertaken so that the wolf would not visit the herd. Sorcerer shepherds were also feared who knew the necessary spells, and knew how to send the wolves to kill another owner’s herd by them. Although it was said that the blessing of sheep was in the tracks of wolves (it was held that if a wolf takes a sheep from the herd it is of course bad, but the sheep will grow well afterwards ). A good farmer’s wife ties at least one pair of mittens to the sheep barn wall, then wolves would not come near the barn.

Shepherds did not eat butter or meat before St George’s day, because otherwise the wolves would kill many animals in the herd in the summer. On St George’s day women knitted socks and were busy with sewing – so eyes were symbolically pierced out of the wolves head, so that it would not see to come to the herd. For the same purpose the shepherds in some places burned juniper bushes. It was believed that that St George’s fires and smoke from juniper had a cleansing magical power – it was good for the health of men and animals and kept wolves off throughout the whole summer. The notice from Iisaku parish in Jakob Hurt’s collection is interesting and unusual:

On St George’s day the shepherd walks the paths to tie the wolf, for which he ties 3 needles with string on spruces, 3 knots on each string. On St Michael’s day he goes to fetch the needles, then the wolf may do damage again. (Iisaku parish, 1888.)

The wolf in place lore

Kalevipoeg, known from Hiiumaa ancient tales and the epic folk saga, threw stones at wolves too and several erratic boulders are known as wolf rocks.

Kalevipoeg, known from Hiiumaa ancient tales and the epic folk saga, threw stones at wolves too and several erratic boulders are known as wolf rocks.

Once a mare with a foal was feeding in a pasture. It was the evening of Midsummer eve. A wolf came to kill the foal. Kalevipoeg who had been walking near the Hiiemägi in Oore village in Ohekaki parish had seen this (it was ten verst away). He grasped a stone and threw it at the wolf but because they were too close to each other all three were hit by the stone. – The foal had a bell round its neck. Now each Midsummer night the tinkling of the bell at the foal’s neck is heard. (Rapla, 1896.)

Near Kallaste village on the Peipsi shore there is a great stone that is called Kalevipoeg’s rock. This rock Kalevipoeg had thrown in pursuit of a wolf that had attacked the sheep flock. Even today the traces of Kalevipoeg’s fingers can be seen on the stone. (Palamuse, 1928.)

Some wolf rocks have been given their names from the belief that an individual turned into a werewolf by witchcraft kept her wolf skin under it, or visited there to suck her child. Some wolf rocks have their name from their particular exteriors.

Hunt or susi?

„Susi” for wolf is allegedly an older word than „hunt“ that is thought to have been one of the oldest words borrowed from Germanic languages. By and by it pushed „susi“ into the background. According to magic reasoning it is believed that using the true name will bring about a meeting with the name-bearer, and so many euphemisms or pseudonyms are used in talking of wild animals. So the name „susi“ has been used as a pseudonym for wolf, "hunt", and the other way about (Hiiemäe, 1969, p 411). But in addition to these two best known words, the wolf has been called, in various dialects, võsavillem, võsaelaja, kriimsilm, vanaonu, vana pikk hanna or pika sabaga mees, pühajürikutsikas, pajuvasikas, metsatöll**. In the Rõuge parish the wolf has even been called haavikuemand which is usually used for hare. In the border areas the wolf name „vilks“ originating from Latvian has also become established. It was believed that if the shepherds named the wolf by its true name near the herd, it would soon be there. It was not considered wise to talk about the wolf by its true name at the table – it was believed that it would then carry off a piglet from the barn or a lamb from the herd.

The full-length article has been published in journal Loodusesõber 2013. February issue.

*Wiedemann's dictionary, first ediiton from 1869, Estonian-German

** wolf pseudonyms: copse-William, copse beast, streak-eye, granduncle, old long-tail or long-tail man, St George’s doggie, willow calf, forest giant

Translation: Liis